Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

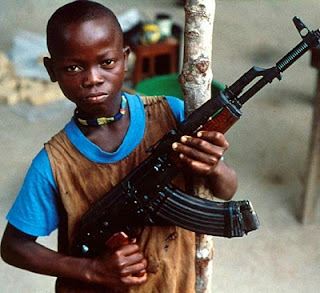

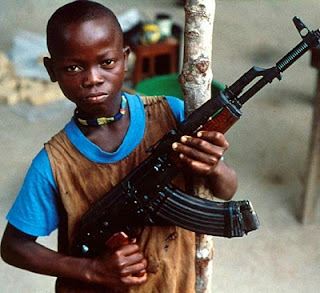

This was certainly true for Jason Russell, Laren Poole, and Bobby Bailey, three young, energetic film students who, in 2003, traveled to Africa in search of adventure. There, they learned about a little-known, long-running war in which children were being abducted and turned into soldiers—sometimes even being forced to kill their own parents.

Many of you know by now what happened next. These guys started Invisible Children, an advocacy group that has created several documentaries and videos to bring attention to these children, including the wildly successful video that has almost 40 million views on YouTube at the time I am writing this. This video was powerful, shocking, and, in my opinion, quite informative, but like anything that gets significant attention, it has also gotten significant criticism: They don't have a plan for what to do after Kony is finally captured. They are only spending 32% of their money on actual aid. Joseph Kony isn't even in Uganda anymore. The video is misleading and oversimplifies the problem.

First of all, of course the video simplifies the issue—you can't get the attention of tens of millions of people if you have to explain every minute detail. However, those who saw the video and became interested can easily research this topic further on their own. While some of these attacks on the IC are blatantly untrue, others are a bit more complicated. Three of the criticisms against the Kony2012 movement in particular really struck a nerve with me.

1. The White Man's Burden

I have read several criticisms of Invisible Children and Kony2012, like this one, that mention that the movement is simply a product of the “White Man's Burden.” These critics present us with a sort of Catch-22: because we are white and privileged, we should feel guilty about the poverty and corruption in the third-world countries of Africa; however, it is wrong to try to help the people of these countries because of course we are only doing it selfishly to relieve our own white man's guilt.

I, for one, do not feel guilty about these problems because I'm white; in fact, I don't feel guilty at all. I feel angry. I'm angry that just because a child is born in Africa, she might have to live in fear of war, kidnappers, and AIDS; I am angry that Joseph Kony and his followers are abducting children from their homes, arming them with guns, and forcing them to kill; and frankly, I am angry that some people can justify ignoring these problems by claiming our aid is nothing more than the “White Man's Burden.” No, I do not feel some deep sense of guilt that I was born into a white, middle class family in the United States of America, and no, I am not outraged by Joseph Kony's horrendous war crimes just because the victims are African. Call me crazy, but these issues upset me because the crimes Kony is committing are crimes against humanity—against human beings—and I could really not care less what shade of brown their skin is.

2. Invisible Children is Just an Advocacy Group

I've seen and heard several complaints that the Invisible Children spends too much money on filmmaking and awareness and not enough on actual aid. First of all, the IC spends about a third of their money on “programs on the ground in LRA-affected areas that provide protection, rehabilitation and development assistance.” But more importantly, I don't understand why people are vilifying advocacy and awareness. As one blogger snarkily comments, “these problems are highly complex, not one-dimensional and, frankly, aren’t of the nature that can be solved by postering, film-making and changing your Facebook profile picture, as hard as that is to swallow.” I disagree. Kony2012's goal is to bring attention to these problems so that the government—and the world—do not ignore or forget about these invisible children. So if changing your profile picture will get your friends to start asking “Who is this Kony guy I've been hearing so much about?”, then I say do it.

The fact is, this video is getting people talking, starting a conversation. And that fact, in and of itself, is a good thing. These guys went to Africa, saw atrocities being committed, asked for support from Washington, and got no help. Then they started spreading the word about these children, got a significant following, and suddenly Washington paid attention. This is the truth about U.S. politics: politicians will listen if they think the people—their voters—care. And not just some voters. A lot of voters. So yes, the IC is amazing at spreading awareness, and yes, this is what a lot of their efforts go towards. I don't understand why this is such a bad thing. I'll admit, I have had an Invisible Children's club at my high school since before I can remember, and it wasn't until I saw this video that I really knew what it was or what it did. So say what you want about the IC or about Kony2012, but we can all agree on one thing—their message is being heard, and it's being heard loud and clear.

3. Why Aren't They Doing This, That, and the Other Thing, Too?

3. Why Aren't They Doing This, That, and the Other Thing, Too?

And finally, the criticism against Kony2012 that is just all too familiar is that the IC is focusing on the “wrong” issues or not addressing enough issues. When I posted my “It Only Takes a Girl” video a couple of months ago, I got critical comments complaining that I didn't talk about male circumcision, or I ignored problems concerning abuse and rape here in the U.S., or I didn't address boys' education, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. My response to those people, and the similar critics of the Invisible Children, is this: one person, one organization, one video, cannot do everything. If you think combatting malaria in Africa is more important than stopping Joseph Kony, great. If you think cleaning up industrial waste and pollution here in the U.S., or eradicating polio, or fighting corruption in the Ugandan government is important—well, you're right. All of those things are important. But that doesn't diminish or disqualify the mission of the Invisible Children. Okay, so they aren't also addressing the issues of Nodding disease or the problem of oil. But these are simply not their mission—at least, not until they complete their current mission of bringing Joseph Kony to justice and providing a basis of support for the children of war. If you care about some other issue and think money should be spent on it instead, then start a charity, make an incredibly powerful video, and collect donations for your cause. But people simply cannot expect the Invisible Children to do it all.

I am all about asking questions and not just accepting things at face value, but I don't think the Invisible Children is the sneaky, devious organization people are making it out to be. Three guys went to Uganda and met a boy who was ready to die, and they made him a promise that they would do everything they could to help. No, it isn't because they are white, and no, they can't do everything. But they can do something—they can tell the world about these invisible children and make sure we never forget. In the words of American author, historian and Unitarian clergyman Edward Everett Hale:

- Margaret Mead

This was certainly true for Jason Russell, Laren Poole, and Bobby Bailey, three young, energetic film students who, in 2003, traveled to Africa in search of adventure. There, they learned about a little-known, long-running war in which children were being abducted and turned into soldiers—sometimes even being forced to kill their own parents.

Many of you know by now what happened next. These guys started Invisible Children, an advocacy group that has created several documentaries and videos to bring attention to these children, including the wildly successful video that has almost 40 million views on YouTube at the time I am writing this. This video was powerful, shocking, and, in my opinion, quite informative, but like anything that gets significant attention, it has also gotten significant criticism: They don't have a plan for what to do after Kony is finally captured. They are only spending 32% of their money on actual aid. Joseph Kony isn't even in Uganda anymore. The video is misleading and oversimplifies the problem.

First of all, of course the video simplifies the issue—you can't get the attention of tens of millions of people if you have to explain every minute detail. However, those who saw the video and became interested can easily research this topic further on their own. While some of these attacks on the IC are blatantly untrue, others are a bit more complicated. Three of the criticisms against the Kony2012 movement in particular really struck a nerve with me.

1. The White Man's Burden

I have read several criticisms of Invisible Children and Kony2012, like this one, that mention that the movement is simply a product of the “White Man's Burden.” These critics present us with a sort of Catch-22: because we are white and privileged, we should feel guilty about the poverty and corruption in the third-world countries of Africa; however, it is wrong to try to help the people of these countries because of course we are only doing it selfishly to relieve our own white man's guilt.

I, for one, do not feel guilty about these problems because I'm white; in fact, I don't feel guilty at all. I feel angry. I'm angry that just because a child is born in Africa, she might have to live in fear of war, kidnappers, and AIDS; I am angry that Joseph Kony and his followers are abducting children from their homes, arming them with guns, and forcing them to kill; and frankly, I am angry that some people can justify ignoring these problems by claiming our aid is nothing more than the “White Man's Burden.” No, I do not feel some deep sense of guilt that I was born into a white, middle class family in the United States of America, and no, I am not outraged by Joseph Kony's horrendous war crimes just because the victims are African. Call me crazy, but these issues upset me because the crimes Kony is committing are crimes against humanity—against human beings—and I could really not care less what shade of brown their skin is.

2. Invisible Children is Just an Advocacy Group

I've seen and heard several complaints that the Invisible Children spends too much money on filmmaking and awareness and not enough on actual aid. First of all, the IC spends about a third of their money on “programs on the ground in LRA-affected areas that provide protection, rehabilitation and development assistance.” But more importantly, I don't understand why people are vilifying advocacy and awareness. As one blogger snarkily comments, “these problems are highly complex, not one-dimensional and, frankly, aren’t of the nature that can be solved by postering, film-making and changing your Facebook profile picture, as hard as that is to swallow.” I disagree. Kony2012's goal is to bring attention to these problems so that the government—and the world—do not ignore or forget about these invisible children. So if changing your profile picture will get your friends to start asking “Who is this Kony guy I've been hearing so much about?”, then I say do it.

The fact is, this video is getting people talking, starting a conversation. And that fact, in and of itself, is a good thing. These guys went to Africa, saw atrocities being committed, asked for support from Washington, and got no help. Then they started spreading the word about these children, got a significant following, and suddenly Washington paid attention. This is the truth about U.S. politics: politicians will listen if they think the people—their voters—care. And not just some voters. A lot of voters. So yes, the IC is amazing at spreading awareness, and yes, this is what a lot of their efforts go towards. I don't understand why this is such a bad thing. I'll admit, I have had an Invisible Children's club at my high school since before I can remember, and it wasn't until I saw this video that I really knew what it was or what it did. So say what you want about the IC or about Kony2012, but we can all agree on one thing—their message is being heard, and it's being heard loud and clear.

3. Why Aren't They Doing This, That, and the Other Thing, Too?

3. Why Aren't They Doing This, That, and the Other Thing, Too? And finally, the criticism against Kony2012 that is just all too familiar is that the IC is focusing on the “wrong” issues or not addressing enough issues. When I posted my “It Only Takes a Girl” video a couple of months ago, I got critical comments complaining that I didn't talk about male circumcision, or I ignored problems concerning abuse and rape here in the U.S., or I didn't address boys' education, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. My response to those people, and the similar critics of the Invisible Children, is this: one person, one organization, one video, cannot do everything. If you think combatting malaria in Africa is more important than stopping Joseph Kony, great. If you think cleaning up industrial waste and pollution here in the U.S., or eradicating polio, or fighting corruption in the Ugandan government is important—well, you're right. All of those things are important. But that doesn't diminish or disqualify the mission of the Invisible Children. Okay, so they aren't also addressing the issues of Nodding disease or the problem of oil. But these are simply not their mission—at least, not until they complete their current mission of bringing Joseph Kony to justice and providing a basis of support for the children of war. If you care about some other issue and think money should be spent on it instead, then start a charity, make an incredibly powerful video, and collect donations for your cause. But people simply cannot expect the Invisible Children to do it all.

I am all about asking questions and not just accepting things at face value, but I don't think the Invisible Children is the sneaky, devious organization people are making it out to be. Three guys went to Uganda and met a boy who was ready to die, and they made him a promise that they would do everything they could to help. No, it isn't because they are white, and no, they can't do everything. But they can do something—they can tell the world about these invisible children and make sure we never forget. In the words of American author, historian and Unitarian clergyman Edward Everett Hale:

I am only one, but still I am one.

I cannot do everything, but still I can do something;

and because I cannot do everything,

I will not refuse to do something I can do.

I just would like to say that I have never been the humanitarian type. I may give money to the occassional homeless person but have never thought about getting actively involved in a cause until I saw this video. Not only did it touch me that three kids from America were willing to take on such an enormous task; it also spoke volumes about what young people like myself can accomplish if we all just come together. I am an educated young black woman and do not feel pity because these are kids from Africa that have to face these tragic circumstances. I feel sorrow because they are KIDS period. I am proud to see that in a country where everyone is only concerned for themselves and have nothing to stand for, hundreds and thousands of young people have found something to stand up for. I am willing to devote my time and money to this organization and if you know any groups that are proactive in the KONY2012 campaign please let me know. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteI totally agree with everything you said about Invisible Children. I found it so disheartening that it seemed as if there was more backlash and criticism from the video than support for it. It especially hard to hear the criticism come from apathetic people I personally know are not interested in any cause. I believe that if your going to criticize a cause at least be interested in something and try to make the world better in some small way. Don't just sit on your couch and complain about how the world sucks.

ReplyDelete